Context Control in Go

Best practices for handling context plumbing.

Published: 2024-02-03

tl;dr

There are three main rules to observe when handling context plumbing in Go: only entry-point functions should create new contexts, contexts are only passed down the call chain, and don’t store contexts or otherwise use them after the function returns.

Context is one of the foundational building blocks in Go. Anyone with even a cursory experience

with the language is likely to have encountered it, as it’s the first argument passed to

functions that accept contexts. I see the purpose of context as twofold:

1. Provide a

control-flow

mechanism across API boundaries with signals.

1. Carrying request-scoped data across API boundaries.

This post will focus on good practices for leveraging contexts with control-flow operations.

A couple of rules of thumb to start.

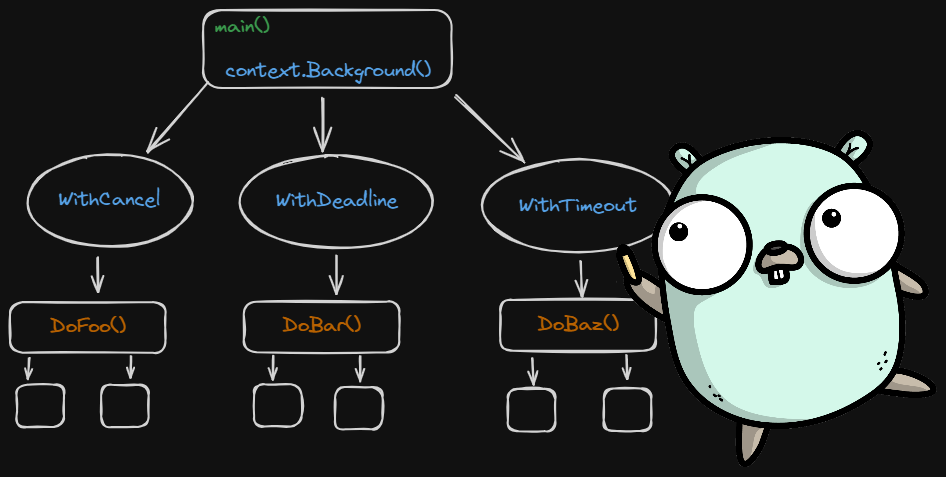

Only entry-point functions (the one at the top of a call chain) should create an empty context (i.e.,

context.Background()). For example,main(),TestXxx(). The HTTP library creates a custom context for each request, which you should access and pass. Of course, mid-chain functions can create child contexts to pass along if they need to share data or have flow control over the functions they call.Contexts are (only) passed down the call chain. If you’re not in an entry-point function and you need to call a function that takes a context, your function should accept a context and pass that along. But what if, for some reason, you can’t currently get access to the context at the top of the chain? In that case, use

context.TODO(). This signals that the context is not yet available, and further work is required. Perhaps maintainers of another library you depend on will need to extend their functions to accept a context so that you, in turn, can pass it on. Of course, a function should never be returning a context.

There are three key rules of thumb when handling context. The first two mentioned above are relatively straightforward. The third rule is the reason for this post, as I encountered it this week.

Storytime

The documentation for context states:

Do not store Contexts inside a struct type; instead, pass a Context explicitly to each function that needs it.

I thought I understood this implicitly, and it sounds easy to obey. So I was surprised

and confused earlier this week when I received a comment on a code review telling me, “Don’t

store contexts.”

“I’m not, though…” was my first thought. No context was in my struct!

What was I doing wrong? Let me set the context (pun intended). If you just want the third rule sans preamble, skip to the next section.

Note: The code samples discussed below are simplified approximations of the issue I faced. While the examples should be fine, there may be typos.

Imagine a long-running routine that makes requests to some source and relays the data it receives to a PubSub service. It keeps doing this until the caller tells the routine to stop. This relatively common system may look something like this:

type Worker struct {

quit chan struct{}

// internal details

}

// New configures and returns a Worker.

func New(ctx context.Context, ...) (*Worker, error)

func (w *Worker) Run(ctx context.Context)

func (w *Worker) Stop()This is fine. However, I (in my infinite wisdom) thought that I could simplify things. I knew

that:

- the caller of this routine would always want to run it asynchronously (I wrote the only caller),

and

- once the routine had been started, the only action the caller would need was to stop the routine.

So, I came up with this:

type worker struct {

quit chan struct{}

// other internal details

}

func Start(ctx context.Context, ...) (cancel func()){

// Configure setup. Details elided.

w := &worker{...}

go w.run(ctx context.Context)

return w.stop

}

func (w *worker) run(ctx context.Context) {

ticker := time.NewTicker(time.Minute)

defer ticker.Stop()

for {

select {

case <- w.quit:

// perform cleanup

case <-ticker.C:

cctx, cancel := context.WithTimeout(ctx, 30 * time.Second)

w.doWork(cctx)

cancel()

}

}

}

func (w *worker) stop() {

close(w.quit)

}Now, most seasoned Go devs would leap out of their seats to tell you it’s an anti-pattern for

libraries to start their own goroutines. Best practices dictate that you should perform your

work synchronously and let the caller decide if they want it to be asynchronous. Despite knowing

this, I figured, “I’m writing the caller; it’ll be fine.” Now, instead of calling New(), then Run(), I can simply call Start(), which returns a cancel

function. And I no longer need to export anything except Start() (I’m a sucker for tiny

API surfaces).

After I did that, I realized, “Oh… I need to ensure I also respect context cancellations.” So I

made this change to run():

func (w *worker) run(ctx context.Context) {

ticker := time.NewTicker(time.Minute)

defer ticker.Stop()

for {

select {

case <- w.quit:

// perform cleanup

case <- ctx.Done():

// perform cleanup

case <-ticker.C:

// do work

}

}

}Again, this should’ve been another indication that my hack wasn’t such a stroke of genius. I had

the same logic to handle context cancellations and calls to stop. However, I was

still too thrilled with my work, so I abstracted the cleanup logic to its own method and moved

on.

Anyway, can you spot how I was storing context even though I only passed it to functions and

never put it in a struct?

The issue is that Start() takes a context, passes it to a goroutine, and returns. Even

after returning, the context it’s passed is still being used, breaking the lifecycle expectations

like I had stashed it in a struct.

So, I assessed my code with some rubber duck debugging:

Me: So, does this mean I have to toss this whole thing and start over??

Rubber Duck: There were some interesting ideas in there. This can work with some tweaks. First off, stop ignoring best practices and make the work synchronous.

Me: That makes sense. It’s two extra characters for the caller to make it async

- not much work. But wait! If Start() is blocking, how will the caller access

Stop()? I’ll have to go back to the New() -> [Run, Stop] way…

Rubber Duck: Well, you currently have two stopping mechanisms that do identical work.

Me: You’re right! A cancellable context is an excellent inversion of control mechanism. I don’t need to create a custom Stop function.

type worker struct {

// internal details. no stop channel.

}

// Start configures and runs the worker.

// Blocks until context cancellation.

func Start(ctx context.Context, ...){

// Configure setup. Details elided.

w := worker{...}

// blocking call to run

w.run(ctx context.Context)

}

func (w *worker) run(ctx context.Context) {

ticker := time.NewTicker(time.Minute)

defer ticker.Stop()

for {

select {

case <- ctx.Done:

// perform cleanup

case <-ticker.C:

// do work

}

}

}By trying to be a little less clever, the final solution was cleaner, simpler, and less error-prone.

Rule 3: Don’t store contexts

The core of the rule is:

When a function takes a context parameter, that context should only be used for the duration of the call, not after it returns.

The rationale is that once a function returns, the caller often cancels the context. Then, any calls made with that context will be canceled before they even begin, causing errors. These can be some of the most obscure bugs to root cause, so it’s best to eliminate the possibility.

Fin.

Additional References on this topic:

-

Contexts and structs

-

Google Go style decisions

-

Google Go style best practices